Should an Asian writer write Black characters?

Kwame Anthony Appiah answers a question from a writer and drills into the politics of identity. My thoughts.

On September 22, an Asian television writer wrote to the New York Times to express reservations about her career writing Black characters. The Times’s ethicist, British-Ghanaian philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah, replied.

When engulfed in Twitter, I’m refreshed to hear what an actual philosopher has to say about identity politics. I would expect the chasm between heart and head to be too great for anybody to find his answers conclusive. Still, here’s what I gather from his response.

You can’t predict the effect of a self-denying ordinance

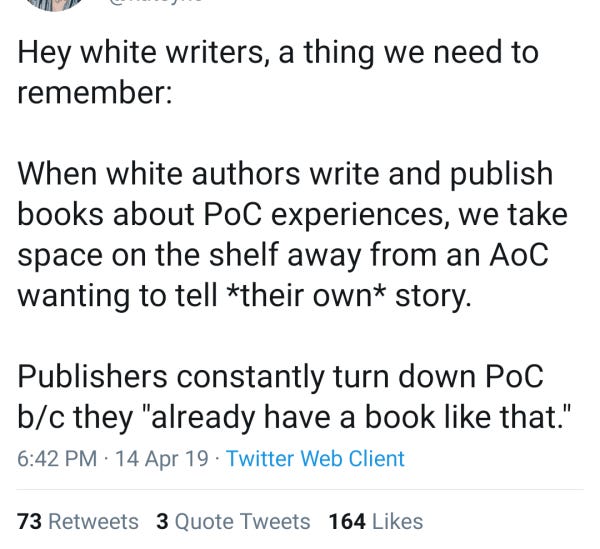

In literary circles, it’s common to hear people talk about privileged writers “taking the space” of a marginalized writer who’s “more qualified to tell their story.”

Is it true? Is a book like Jeanine Cummins’s American Dirt taking space away from a Latina writer who isn’t getting a chance in the marketplace? Appiah suggests a more nuanced reality:

Given that you don’t control who will get the jobs you decline, you have no reason to think that avoiding projects with Black leads will result in their being handed to a Black writer.

Most shows, as you indicate, never get out of development. If you’re really good at your job, though, your writing could make it more likely that a project actually goes into production — creating more opportunities for Black actors, staff writers, filmmakers, animators and so on.

The point is that you can’t predict what the net effect of an individual self-denying ordinance would be.

In logical reasoning, the idea that marginalized writers don’t see publication because privileged writers take up space falls under the false effect fallacy:

X apparently causes Y

Y is wrong

Therefore, X must be wrong.

In this case:

Privileged authors writing books about marginalized characters apparently denies marginalized writers space

Denying marginalized writers space is wrong

Therefore, privileged authors writing about marginalized characters must be wrong.

The logical fallacy lies in the fact that X only sometimes causes Y and X isn’t always wrong.

X only sometimes causes Y. We cannot establish the claim of causality as certain in all cases. Privileged writers taking up space may be a reason marginalized writers have difficulty getting published — but dozens of systemic reasons keep marginalized writers behind the eight-ball.

X isn’t always wrong. Even if privileged people writing is a cause and not the only cause of the industry denying marginalized people access, why not remove the barrier? Because there are consequences to this, too. That thinking would have denied us The Good Earth — a story about Chinese people by my fellow West Virginian Pearl S. Buck — as one example. It won a Pulitzer. She won a Nobel Prize. It’s a wonderful book. Nobody else could have written it, and I’ll die on that hill.

In short, and to Appiah’s point, by not telling a story, there’s no guarantee that a marginalized writer will get the space to tell theirs. Just because somebody else might be more qualified to tell a story doesn’t mean they will tell the story, or tell a better story, or tell your story — which may need to be told.

A writer should stay in their f/cking lane.

Sensitivity to differences — or maybe a desire for society to see an individual as “good” and not to get yelled at on Twitter — has led to a lazy conclusion: only X should write about X. People need to “stay in their lane” and “write what they know.”

This thinking triggered the initial question to Appiah. He concludes,

We don’t want an approach in which writers and characters must match up, one to one, in their racial or ethnic identities. That way lies a system in which Shonda Rhimes doesn’t get to write a series centered on the white surgeon Meredith Grey; in which George Eliot (being neither male nor Jewish) doesn’t get to tell the story of Daniel Deronda. Pretty soon, all storytelling would be confined to autofiction.

That’s not quite how the argument plays out in the real world, though. It upsets nobody when Shonda Rhimes writes a white character. The argument, on its surface, is “only x should have license to write about x,” but in reality there’s a less-discussed structural rule: if X has more privilege than Y, and Y has more privilege than Z, then X can write about X; Y can write about X and Y, and Z can write about X, Y, and Z.

By those rules Shonda Rhimes, a Black woman, can write a story centering a white character with much easier license than a white woman can write a story centering a Black character. Not everybody is Shonda Rhimes, though, and many Black authors face a different related challenge:

The access and constraints of an “identity permit”

To be sure, what’s sought, in the guise of expertise, is often something else: Call it an identity permit. An identity permit doesn’t need to be cashed out by experience. Conversely, if you lack an identity permit, putting in the work might not matter.

“Permission” to write about certain people and certain scenarios has little to do with research, understanding, or even lived experience. Appiah calls the license to write about certain identities an “identity permit,” and it is as prohibitive as it is permissive. He includes stories of people in different scenarios with different “permissions.”

A Black author finds success writing about Harlem, where she only visited, but readers reject her book about her lived experiences in the white Connecticut town where she grew up.

A successful white writer can’t find a publisher for her well-researched book with a Black protagonist set in 19th century America.

A Black writer writes a successful story of an escaped slave in 1830s Barbados, but is no more a part of that world than the white woman, above. Her hard work and accurate research shrink under the assumption she knows the world — and is somehow part of it — because she is Black.

Somewhere, here, is the rub. Saying “only X can write about X,” may remove competition between privileged and marginalized writers on one level, but shackles marginalized writers in a different way. Publishers can see them as good only for writing about “their own kind.” While white writers write of wizardry, an Indian writer who wants to write a book about swords and sorcery seems valuable to the industry only if they write an Indian wizard, or base it on the Vedas or subcontinental mysticism.

My conclusion is what it always has been in matters of identity in writing. When we push toward maximum equality, with everybody given equal access to publishing, it helps everybody — not just marginalized writers. It removes boundaries and “permits” for all writers. When you know you can write about anything with an equal chance of getting published, it doesn’t matter if the person next to you is “in your lane.”

Equality is good for everybody.

You can find the original article here: I’m an Asian TV Writer. Should I Take on Projects With Black Leads?

CT Liotta is author of NO GOOD ABOUT GOODBYE, a YA LGBT coming-of-age adventure available November 24, 2021.